Paleontological Breakthrough: New Dinosaur Species with Unique Crest Discovered on White Island

Scientists from the United Kingdom have announced a groundbreaking discovery that could reshape our understanding of the fascinating prehistoric world of dinosaurs.

The Natural History Museum in London revealed the discovery of a new species of iguanodontian, a group of herbivorous dinosaurs that roamed the Earth over 120 million years ago during the early Cretaceous period.

Previously, it was believed that the fossil remains found belonged to two already known species.

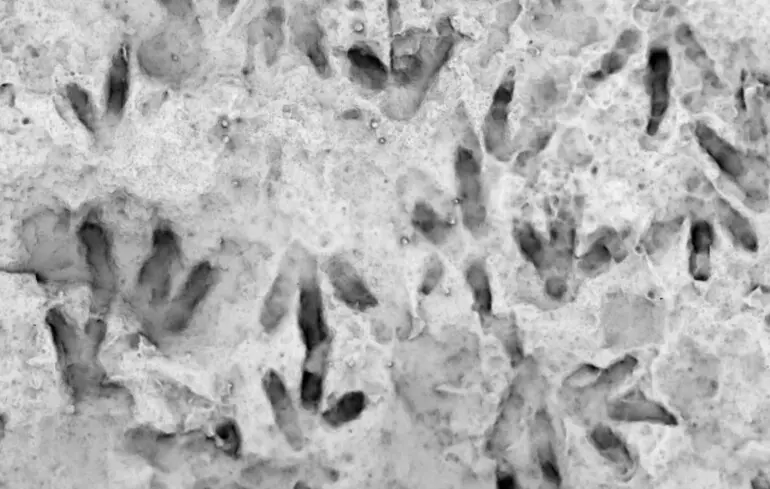

However, during a re-examination led by retired researcher Jeremy Lockwood, scientists uncovered a crucial feature: one of the bones displayed exceptionally long nerve spines.

This morphological characteristic distinguished the newly identified species, which has been named Istiorachis macarthurae, honoring British record-breaking sailor Ellen Macarthur.

The fossils were excavated on White Island, situated off the south coast of England, a site that was teeming with development and ecological diversity around 120 million years ago.

According to researchers, this new species stood about two meters tall and weighed approximately one ton.

Its unique physical traits offer valuable insights into the evolution of iguanodonts and the biodiversity that existed on the island during that time.

The discovery underscores the significant diversity within early Cretaceous herbivores and highlights White Island as a key region for paleontological research.

While the exact function of the crest along the dinosaur’s back remains uncertain, hypotheses range from visual attraction and mate display to species recognition.

Lockwood explains that the evolution of iguanodonts saw a gradual increase in size and structural complexity, with this crest likely playing a role in sexual signaling or social dominance.

He dismisses the idea that the crest was used for thermoregulation, as its rich blood supply would have made it vulnerable to attacks.

Most plausibly, the structure served as a visual signal for attracting mates or intimidating rivals, similar to the extravagant tail feathers of peacocks.

This discovery complements previous findings in Chile, where paleontologists uncovered a fossil of Yeutherium pressor—an extinct mammal that lived 74 million years ago, notably smaller than a mouse.

These groundbreaking finds illustrate the incredible diversity and evolutionary pathways that shaped the prehistoric ecosystems.