Deep Crisis in Ukraine’s Architectural Education: Challenges, Flaws, and the Path to Reform

In current Ukraine, where war continues to reshape landscapes and pose new challenges to the nation, particular attention is drawn to the system of training future architects.

The reconstruction of cities, creation of shelterings, and development of public spaces all require highly skilled architects who do more than just possess artistic sensibility—they must have an in-depth knowledge of regulations, the ability to work collaboratively, manage large-scale projects, and bear responsibility for their results.

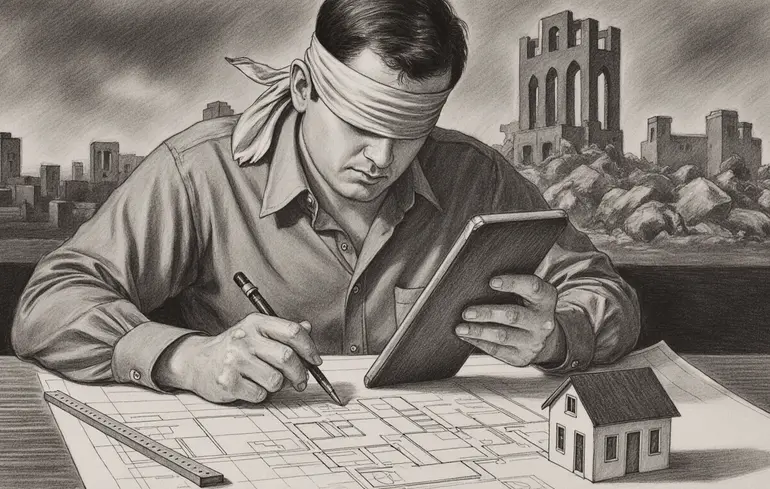

However, the Ukrainian architectural training system faces profound systemic problems.

These issues became especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic when education shifted online.

For architecture, such abrupt changes proved damaging—loss of hands-on experience with models, projects, face-to-face consultations, and practical skills hindered students’ readiness for real-world challenges.

After the outbreak of full-scale war, the situation worsened.

Many students and young professionals had to relocate, seek shelter, or assist in volunteer projects aimed at recovery.

This period underscored the critical need for trained architects capable of rapid response and community-driven development.

A deeper systemic flaw lies in the disconnect between theory and practice.

Educational programs often separate theoretical knowledge—lectures, history, design theory—from practical skills like project development, modeling, and regulation interpretation.

As a result, graduates enter the labor market without essential real-world understanding.

They are forced to learn many skills on the job, which slows their professional growth.

Addressing this requires urgent curriculum reform.

Modern private architecture schools demonstrate a more current approach—they invite practicing professionals as lecturers, implement accredited programs aligned with market demands, and accept smaller student groups, enabling closer mentorship and higher quality education.

Despite higher costs, they prioritize quality over quantity.

Meanwhile, traditional universities tend to maintain conservative curricula, hindered by bureaucracy, outdated teaching methods, and minimal engagement with practitioners.

Consequently, many young architects resort to informal education—creating personal courses, delivering lectures on independent platforms, or conducting workshops—to stay abreast of trends and skills.

The core of contemporary architecture is a fusion of art, engineering, and functionality—not just forms or facades.

It should reflect values, shape environments for human activity, and address pressing issues like sustainability and resilience.

Achieving this requires systemic reform—updating legislation, revising standards, and fostering innovation.

Currently, Ukraine’s legislative process is slow, often requiring formal petitions and paperwork even in critical situations.

For example, the recent rapid development of norms for shelters illustrates the problems in legislative agility.

The absence of a clear vision for Ukraine’s future also hampers progress—without a long-term strategic outlook, reforms stagnate.

The future of Ukrainian architecture hinges on transforming education from a mere reproducer of templates into a space promoting critical thinking, responsibility, and practical skills.

Students should graduate with understanding that they shape not only buildings but also societal environments, contributing to the country’s future.

If these changes are implemented today, within a decade Ukraine will not only have reconstructed cities but also a generation of architects capable of shaping the future rather than merely catching up with the past.